Progressing Your Pitch

Cashing in on earned trust

The first four years of my Microsoft career were contributing to Windows 3.1, Windows 95, and Internet Explorer 3 (IE3). My area of expertise had been UI (User Interface) controls (e.g. button, scrollbar, listbox, and treeview). After IE3, I connected with Ian Ellison-Taylor and Microsoft’s Java team. From my experience with controls, I wanted to experiment with a compositional model for controls. Rather than each control being its own separate world, there would be a common base element that all controls, from simple to complex, would be composed of.

The two main points of my pitch were that (1) I could rebuild Windows’ library of controls (there were a dozen different controls at that time) in Java in three months, and (2) they would be richer in functionality due to them all sharing this same element-based construction. It played out well, and I still recall the 1996.12.13 deadline because I hit it … to the day! 🥳 There were some rough edges with this first implementation, but it was an important stepping stone for what came next.

After releasing a couple versions of Microsoft’s Java, our UI team moved back into Windows. The compositional model for UI was already picking up steam there, where HTML was being used in this compositional fashion. The problem was that HTML was a more general purpose framework, and was heavier weight because of that. So the parts of Windows that were written in HTML were benefiting from the customizability of compositional controls, but they were hitting significant performance problems.

This led to a relatively big idea in 1998. Still under Ian, I pitched the idea that what we had been experimenting with in Java in 1996 and 1997 was applicable to the Windows space now, and that we could build a special purpose compositional UI framework that would give Windows all the benefits of HTML without the performance problems. Ian gave me the green light, and I partnered with Jeff Stall and Mark Finocchio, who were both already building relevant pieces, to build Direct UI.

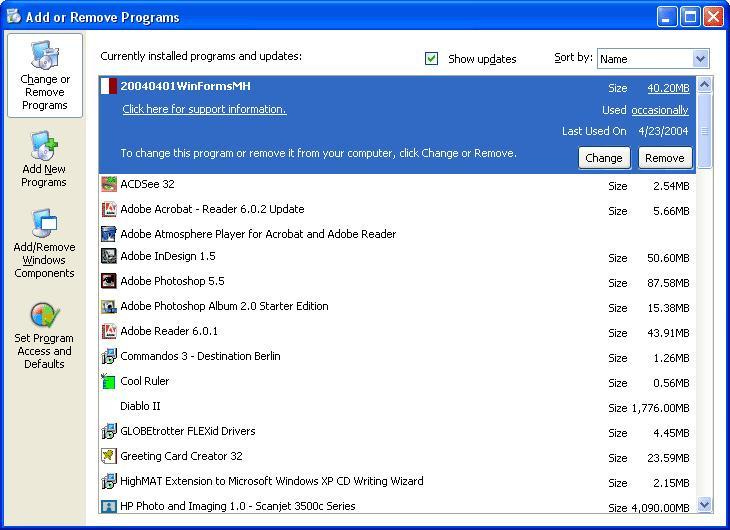

To test the readiness of our framework, we took the most demanding Windows experience that was currently written in HTML, “Add/Remove Programs”, and built a feature-for-feature equivalent in Direct UI.

We put the two side-by-side to present to the Windows Shell team, several individuals I had worked with in my first four years. We first had them look at the app and play with it, to prove the functionality was all there. Then we highlighted how much quicker our version rendered, with the HTML version drawing in waves: the text appeared first, and then the items shifted as the icons appeared later. For the grand finale, we showed them the memory being used by both. The DirectUI version was 1/10th the size of the HTML version.

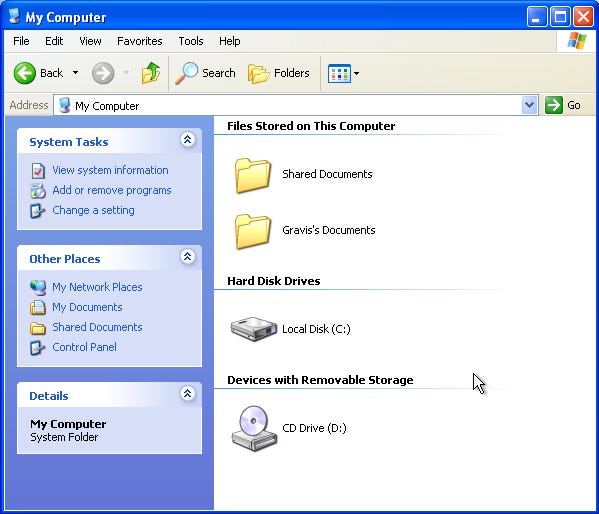

They were impressed with what they saw, but they were also nervous about an unproven technology. So they asked us to prove it with two move experiences: the Task View of File Explorer, and the new Login experience. There were now six people involved in the DirectUI effort. We nailed both in pretty short order, showed them the results, and they were sold.

This success created a collision between our Direct UI team and Microsoft’s HTML team, which led to another opportunity for a pitch. HTML is a standard that we don’t control, being “governed” and evolved by a web consortium. Microsoft’s HTML implementation was one of several implementations in the market, and to be competitive, it had to be as compatible as possible with this moving target. In my pitch, I argued that this compatibility is the reason for all the performance challenges we were facing with HTML, and we should build our own compositional UI framework that we can control and tune.

This pitch framed a two month debate about the best path forward for Microsoft. In the end, the HTML team and the Direct UI team joined forces to create the Windows Presentation Framework team, a 200 person organization dedicated to building a new UI framework.

This is one example of how bottom-up leadership drives direction in an organization1. It also shows the fuel that drives bottom-up leadership: the pitch. You have a theory, so you test the theory out. If you have success, then you need to pitch your idea to get broader adoption. A successful pitch begets bigger pitches, with increasingly broader scope. The above arc grew from one person to three people, then six people, and then 200 people.